By Michael Zingone and Alex Zhou

(This article is a cross-post with a Medium article I published for my school’s Winter Data Competition. We were later reached out to by Analytics Vidhya so it could be used under their Medium publication!)

Introduction

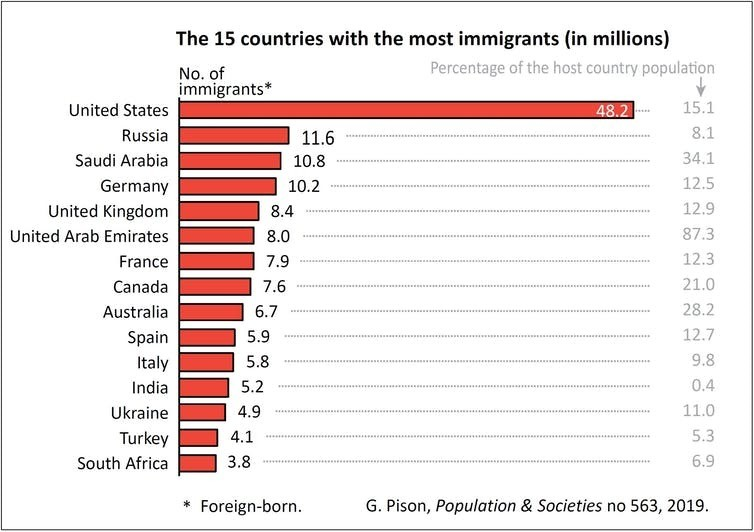

The United States has the largest foreign-born population of any country in the world. The next largest, Russia, hosts a migrant population nearly five times smaller, setting the U.S. apart as a genuinely special case of international movement. Historically, the largest sending country of immigrants to the U.S. has been Mexico by an overwhelming margin, with more than 24% of the entire Mexican population worldwide currently residing in the U.S. (that’s including all Mexican-origin people currently living in Mexico).

Image: Gilles Pison, based on United Nations data

To understand why one way Mexico-to-U.S. immigration is so common, we would do well to examine the U.S. immigration policy, which has been known for extending preferential treatment to family ties. This policy, combined with a particularly lax historical definition of family, has led to our significant migrant population and global notoriety for being a relatively open-borders nation. Between 1980 and 2000, the number of Mexican-born people in the U.S. shot up by 450%, even as our borders became increasingly militarized.

It is critical that we eventually arrive at a satisfying and fair resolution to the immigration question — not only for the 11.1 million undocumented immigrants currently residing within our borders, but for their families, friends, and others who are affected by their uncertain status and the intense, highly partisan debate that surrounds it.

Why Migrate?

Many theories have emerged to explain why the southern U.S. border is the most often crossed international boundary in the world. There are a variety of socioeconomic factors that contribute to making migration to the U.S. particularly attractive. However, in this article, we’ll examine a small but steadily growing body of research that reveals a surprising, oft-overlooked factor in the decision to migrate from Mexico: climate change.

The argument is actually very simple — so simple, in fact, it’s almost surprising that it hasn’t been discussed more: First, we know that climate change has already measurably altered annual weather patterns, and that these effects are more pronounced for nations closer to the tropics (despite those nations having contributed least to the problem). We also know that extreme weather and rising temperatures can reduce crop yields through desertification and natural disasters. Intuitively, we should then also predict that this reduced farming viability will lead to farmers looking for work elsewhere, possibly even across international borders, and likely taking their families along with them.

If true, the implications of this climate-driven migration theory are substantial. First, understanding this theory would do much in the way of fighting anti-immigrant sentiment, seeing as how wealthier countries are largely responsible for the emissions that are causing climate change, which will disproportionately affect tropical countries with less resources to handle extreme weather in the first place; if high levels of immigration are a scapegoat for other internal problems, we would be at least partly to blame.

Second, it would indicate that anthropogenic climate patterns have likely already influenced global movement, since average temperatures across the world have measurably risen from human activity. Third, we would be safe in adding further human displacement to the growing list of predicted consequences of future global warming.

Analysis and Predictions

Our analysis first sought insight into possible correlations between crop yields and immigration patterns from Mexico to the United States. The data we used in the analysis to follow comes from two sources: a MigrationPolicy.org article providing state level data on Mexican migration to the U.S. from 2004–2015 and Ureta et al.’s research paper detailing Mexican corn crop yield over the same time period.

We selected corn as the crop of interest for two reasons. First, corn is by far the most important crop grown in Mexico, accounting for about 60% of its cropland. Second, a study on the effects of temperature increases on crop yields found that corn/maize is most temperature-sensitive out of all the major crops. These facts, combined with the unique case of Mexico-to-U.S. immigration, make the country an especially interesting target for climate migration analysis.

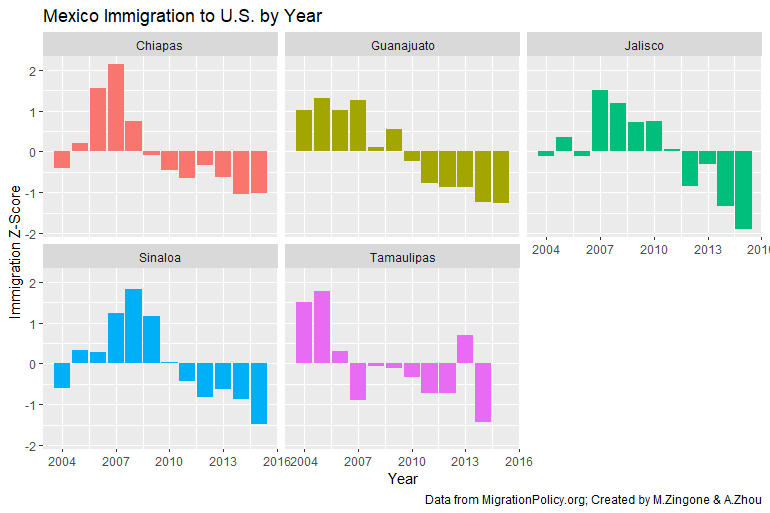

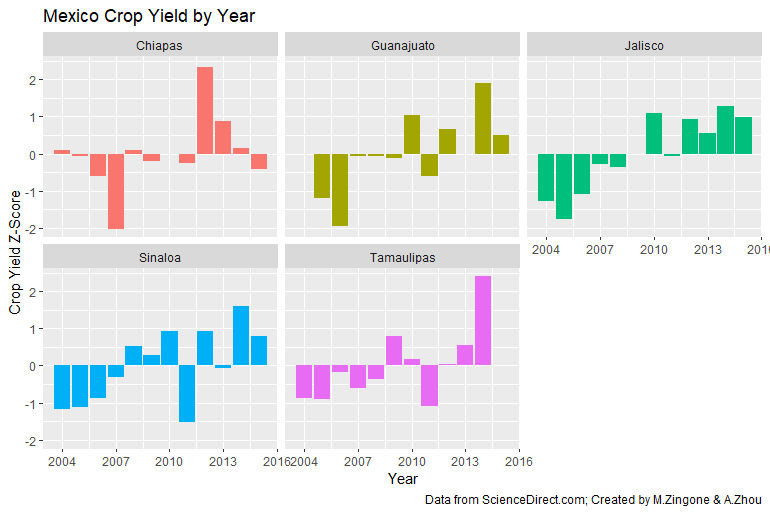

We first explored the data through visualizing standardized immigration and standardized crop yields from 2004–2015. The below two charts illustrate these time-series trends for five major Mexican States for which we had data.

The state-specific trends here are striking. For every state, the peaks in immigration — generally speaking — correspond to the lows in crop yields. In other words, when the harvest doesn’t do well, people seem to want out.

Crop yields, by definition, are a measure of land efficiency. It measures how much crop was produced per given area of land. This efficiency metric allows us to compare yields over time in case the absolute farmland area used has changed. It also allows us to avoid the conflating the relationship between immigration simply reducing the overall agricultural workforce with environmental crop efficiency affecting outward migration.

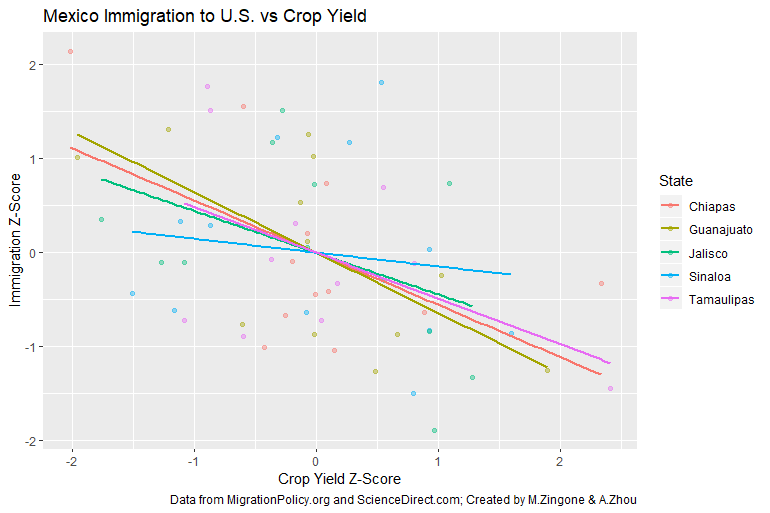

To further investigate this relationship, we plotted the standardized immigration and standardized crop yields against each other. The results below show a clear trend: the lower the crop yield, the higher the immigration in that particular year.

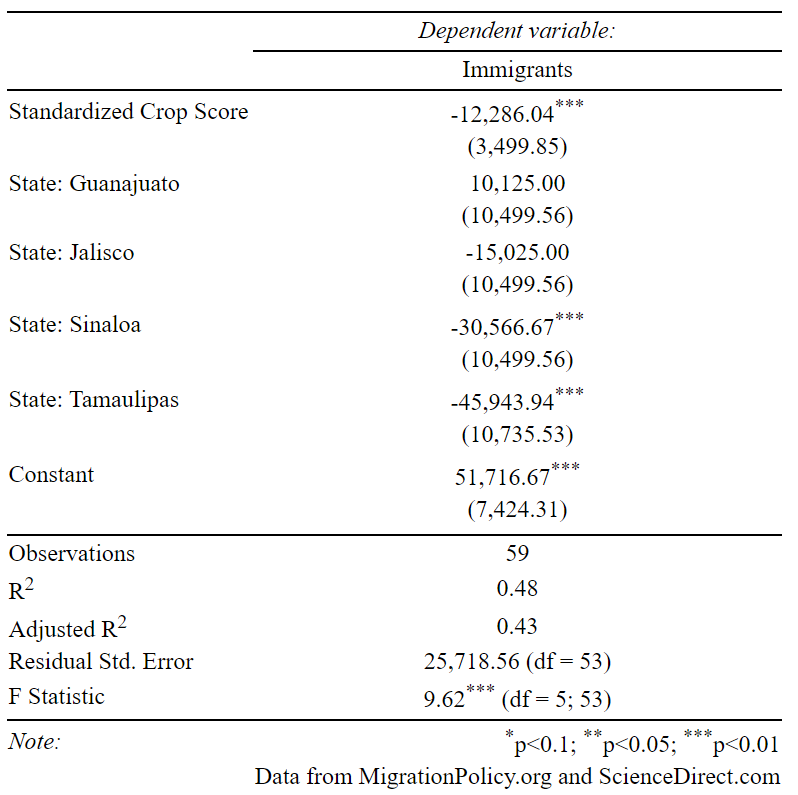

Finally, we ran a simple linear regression to predict immigration based on crop yield (standardized), including States as dummy variables in our model. The results show a statistically significant relationship between crop yields and immigration, accounting for State-specific immigration trends.

Per the model above, we see that for every one-unit increase in the z-score of crop yield, we can expect, on average, approximately 12,000 fewer immigrants from Mexico to the United States. Conversely, a similarly sized decrease in crop yield would indicate an expectation of ~12,000 more immigrants. Standardized crop yield is a statistically significant variable at the 0.01 level of significance. While we are unable to definitively establish a causal relationship due to the limitations of this study, we can conclude there is evidence of a strong relationship between crop yields and immigration patterns.

Final Thoughts

If we utilize previous established estimates of a decrease of 7.4% in corn yields per increase of a degree celsius, we would arrive at a projected decrease in corn yields of around 6.66% to 16.28% by 2025, and up to 29.6% by 2050 (based on current best estimates of warming in Mexico). Based on our model, these reductions in crop viability could displace an additional 50000 people per year based on decreases in crop yield alone.

Of course, there are many limitations to extrapolating this prediction, but the above analysis and past studies have painted a dire picture of what’s to come for climate-related displacement in Mexico and globally. However, there are many ways that governments could help mitigate some of the displacement that we predict will be caused by climate change.

In fact, there’s evidence to support that Mexico is already aware of the issue and is looking for solutions. Mexico is the only developing nation that has submitted three national communications to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, showing a strong administrative interest in addressing climate-related issues.

To formulate an effective plan, it will be crucial for governments to understand exactly how climate change can affect crop yields. According to its Third National Communication, Mexico is expected to undergo the following meteorological changes pertinent to agriculture:

- Increases in temperature — by 2025, projected temperature increases in the summer are in the range of 0.9 and 2.2°C, and up to 4°C by 2050. These temperature increases will especially impact the Central and Northern parts of the country (for reference, Zhao et al. found that just a 1°C increase in temperature corresponds to a −7.4% average decrease in Maize production, Mexico’s most important crop by far).

- Reduction in precipitation — rainfall is projected to decrease by around 5% in the Gulf and up to 15% in Central Mexico by 2025. By the end of the century, these changes will result in a decline of up to 9.16% in the available water for groundwater recharge and runoff by the end of the 21st century.

- More frequent and severe extreme weather events — severe storms and droughts will increase in number and intensity. By 2025, sea water temperatures will rise between 1 and 2°C, leading to stronger and more intense tropical hurricanes in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico and the Mexican portion of the Pacific Ocean, with a projected increase of 6% in wind intensity and an increase in precipitation of 16% within a radius of 100km from the center of a hurricane.

Former Mexican president Felipe Calderón said, “Mexico is uniquely vulnerable to climate change.” The country is losing 400 square miles of land to desertification each year, forcing an estimated 80,000 farmers to migrate. The country is also facing intense flooding, especially in the state of Tabasco, which decreases water supplies, and an increased hurricane risk as a result of climate change.

Even as Mexico passes legislation (e.g. the Migrant Law amendments in 2012) that eases processes for immigrants from Central America to enter the country, the U.S. has been making it increasingly difficult to enter, removing more unlawfully present immigrants and scaling up efforts to catch recent arrivals close to the border. The U.S. deported a record 409,000 immigrants in 2012.

Countries that are closer to the polar regions, which are projected to be less affected by climate change, should begin to prepare for an influx of migrants seeking refuge from extreme weather, natural disaster, and poor crop viability due to climate change. In particular, the US may want to extend the protections of the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to apply to climate change-related effects, rather than the narrow scope of natural disaster and armed conflict.

People have a plethora of reasons for migration. In the case of Mexicans immigrating to the U.S., reasons can range from political tensions to economic downturns or, as shown through this analysis, varying crop yields. As global warming impacts Mexico in the coming decades, agricultural viability — or a lack thereof — will continue to become a more pressing issue for the average Mexican citizen. Climate change will surely impact future generations in more ways than we can predict today. One thing for certain, however, is that immigration ought to be on the forefront of topics discussed regarding our changing climate.